Sakurai on Sequels

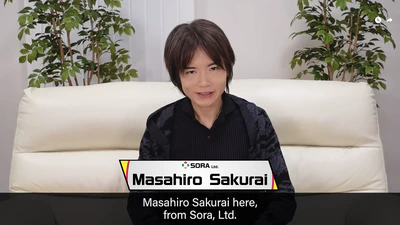

Fans of Nintendo games–and perhaps games in general–are likely familiar with the name Masahiro Sakurai. He’s a game director that’s become something of a household name, given he’s the creator of the Kirby and Super Smash Bros. series, and has become the de facto spokesman for the latter. He also ran a YouTube series titled Masahiro Sakurai on Creating Games, in which he covered a variety of lessons about creating games that he learned over his 35+ year career. Most recently he’s been directing Kirby Air Riders, the long-awaited sequel to 2003’s Kirby Air Ride, and one of the year’s big flagship titles for Nintendo’s newest console, the Nintendo Switch 2.

Everything is Here

Since the Nintendo Switch 2 launched earlier this year, Nintendo has been hosting presentations on their YouTube and Twitch channels to dive into the new console’s big exclusive releases. In what has become his usual style, Sakurai himself personally hosted the presentations for Kirby Air Riders. Near the end of the October 23rd presentation (the final presentation before the game’s release), Sakurai said something that stuck with me:

In this day and age, creating a game and bringing it to life takes a surprising amount of effort. But I think that’s reflected in the final product, so I hope you enjoy it.

I do believe the passionate support from fans was a big reason why this game was made. You have to spend time and money to make games, so those wishes aren’t always granted. And that thanks to that support, and the efforts of a great many people, we were able to make this game a reality.

Just so you know: we’re not planning any DLC. Everything is here. Also, I’m not planning on making this an ongoing series. I’ve thrown everything I have into this game from the start. So I hope you don’t miss this opportunity.

In an era where post-launch content updates, season passes, and triple-figure “deluxe editions” have become commonplace, it’s highly unusual to release a high profile game without any DLC. And in an era where publishers are increasingly risk-averse to original IPs, instead funding sequels and remakes of established franchises, it’s also highly unusual to outright say there are no sequel plans. Yet Sakurai makes a bold proclamation: “Everything is here.” To me, this means they were able to put everything they wanted into this game. For modern games, it’s common to pare down a game’s scope by saying “we’ll save this idea for an update,” or “we’ll save this idea for DLC,” or even “we’ll save this idea for a sequel.” Here, Sakurai is saying nothing was saved for later. Everything is here.

The Sequel Process

This isn’t the first time he’s done this, either. Previously Sakurai also directed Kid Icarus Uprising, which released in 2012 (over 20 years after the previous Kid Icarus game). It was a bold and delightful adventure, so fans and press alike were expectant that it would turn into a series. However, even back then, Sakurai gave an interview with IGN that echoed his Kirby Air Riders comments:

If […] you mean to ask if there’s a sequel, the answer is no. Because we pushed a lot into the game in order to let people have this short yet deep experience, but the novelty of that would likely grow thin in the next game. For now, my thought is that perhaps we’ll see someone else besides me make another Kid Icarus in another 25 years.

On Uprising’s ninth anniversary, Sakurai posted online that although he’s received numerous requests from fans for a sequel or remake, neither was likely going to happen. The reason is what Sakurai considers an often-overlooked aspect of sequel development: they require as many resources to produce as any other game. After he departed from HAL Laboratory in 2003, Sakurai gave an interview with Nintendo Dream that mentions this:

It was tough for me to see that every time I made a new game, people automatically assumed that a sequel was coming. Even if it’s a sequel, lots of people have to give their all to make a game, but some people think the sequel process happens naturally.

I must admit I, too, have had this mentality before. After playing a new game, it’s almost natural to say “that was great, I hope they make another.” Even when playing retro games it’s common to hear “that was great, why didn’t it ever get a sequel?” And while it may be true it’s easier to convince a publisher to fund a sequel to a successful game than take a chance on something brand new, making any game takes a tremendous amount of effort.

Sakurai knows better than most how difficult it is to make a game. Resources (time, money, and talent, among others) are extremely hard to come by, and he actually doesn’t have access to many resources without publisher support. Sakurai’s company, Sora Ltd., isn’t actually a game studio, but more of a consulting firm. When Sakurai is approached by a publisher to direct a game, they also provide him with a team to do the development. For Kid Icarus: Uprising, Sakurai was approached by Satoru Iwata (then-president of Nintendo) to develop a launch title for the Nintendo 3DS. Nintendo and Sora Ltd. then jointly formed a new studio, Project Sora, that developed the game and was promptly disbanded upon the game’s completion. Sora Ltd. can’t produce any games without publisher support, and for one reason or another, Nintendo seems uninterested in dedicating resources to an Uprising sequel or remake, even though there has been noticeable demand from fans.

Balance

In fact, resources had been an issue for Sakurai since Sora Ltd.’s founding. Starting with Kid Icarus: Uprising, all of Sakurai’s games were made by Nintendo’s request. Kirby Air Riders is no exception: in the first presentation about the game, Sakurai says the game was a specific request from Shinya Takahashi (Nintendo’s head of software development) and Satoshi Mitsuhara (then-president of HAL Laboratory), and Bandai Namco was selected as the development studio.

Of course, Sakurai founded Sora Ltd. knowing resources would be an issue. He highlights this problem in his interview with Nintendo Dream:

With times as they are, it’s really difficult to make any money for yourself, and I know that I’m taking a big risk here. It’s entirely possible that I could just fade right away without ever seeing the light of day again. But even if that happened, I’ve already decided to myself that I should keep on doing the work I can do, even if it’s not all about games.

He continues:

If I want to keep producing games as a business, then staying at HAL would be a more stable place to do that. HAL has its advantages. I get a reasonable amount of pay, living in Yamanashi prefecture isn’t that bad, the rent’s cheap, and I get national insurance, you know?

But I don’t care about that sort of stability. Right now I’m far more concerned about the fact that the game industry, which is built from the balance between developers, publishers, and users, is beginning to fall apart at the seams. I think it’s possible for me, as a developer, to have people think about this problem through the development work I do. If I stay in one spot, then I can only communicate this to a limited number of people around the company, but if I can go out and reach more people, I think there are lots of people with far greater abilities than myself out there in the world. I mean, I’m entirely focused on games and I really can’t do all that much myself, but if I can get in touch with people that have other great talents, then I think that will set off a chemical reaction and in the end we’ll have a chance to make new games and better things. People with these talents might be at a loss at what games to make, and perhaps I can help make up for that in exchange for lending me their talent. This may sound idealistic, but it’s really what I think.

The “balance between developers, publishers, and users” offers an interesting insight into professional, big-budget game development. Developers need to deliver great games to users and sustainable profits to publishers; publishers need to supply developers with the resources they need to succeed so the users will be willing to open their wallets. Sakurai mentioned the balance had been falling apart all the way back in 2003, but it’s gotten far worse since then. The cost of producing blockbuster titles has gone up exponentially, increasing developer reliance on publishers to provide a budget. Publishers are wringing users dry by releasing incomplete games for higher prices, plus with paid DLC and microtransactions on top of that. The gap between these development studios and users has grown even wider, with user satisfaction increasingly taking a back seat to keeping publishers happy. And despite (or perhaps because of) these changes, publishers are still struggling. Even Ubisoft, one of the mainstay publishers of the past several decades, is in trouble. For a “triple-A” game like Kirby Air Riders to exist as the best version of itself, rather than a lay-up to a future, superior version, could be considered a miracle.

To reiterate what Sakurai said during the Kirby Air Riders presentation: “[…] the passionate support from fans was a big reason why this game was made. You have to spend time and money to make games, so those wishes aren’t always granted.”

Opportunity

When Sakurai said “I hope you don’t miss this opportunity” while presenting Kirby Air Riders, the “opportunity” he mentioned becomes apparent when you consider the circumstances surrounding the game. It’s rare that a game with lukewarm critical reception and lackluster sales would receive a sequel over 20 years later. It’s rare that, in the age of patches and DLC, a game would release with all of its planned content on day one. It’s rare that Sakurai has access to the resources he needs to deliver his vision (especially outside of the Smash Bros. franchise). It’s rare that one of the world’s biggest video game publishers would ask for a game to be made specifically because the fans asked for it. It’s rare that a game developer gets the chance to make the wishes of fans come true. It’s quite possibly the last Kirby Air Ride game we’ll ever get, and given how stressful creating games has become for him, it could be one of the final games of his legendary career.

I hope you don’t miss this opportunity.